Bastian Vollmer

Professor of Social Sciences

Catholic University of Applied Sciences Mainz (CUAS Mainz)

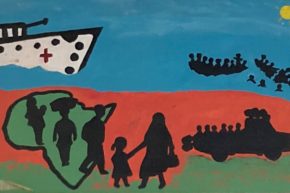

As the past few months have shown, European countries are still struggling to find sustainable migration policies, caught between re-nationalisation of borders and European/EU solutions: Austria, Czechia, Slovakia and Poland have just reinstated border controls at EU-internal borders; the Mediterranean island of Lampedusa, site of an overflowing major refugee camp, has declared a state of humanitarian emergency, etc. These events are accompanied by public debates in the media and political arenas which are dominated by long-established, seemingly unchanged narratives about migration and migrants: we note the criminalisation of migration in the justification of border controls, perpetrator-victim reversal in the case of thousands of migrants dying in the Mediterranean, or the economisation of the resources vs a human rights debate.

Alternative narratives can seem difficult to hear amid the overwhelmingly negative discourse surrounding migration. However, this is a problem inasmuch as less dominant and less foregrounded narratives are crucial to an inclusive democracy. Often, such alternative narratives are tied to the voices of those with less power, resources or access to the media. Pluralist societies benefit from the diversification of narratives, from the challenging of hegemonic narratives by counter-narratives. Liberal democracy and public discourse need the broad participation of all parts of the population in order to develop solutions to pressing issues that, ultimately, have high levels of legitimacy across economic, cultural, religious or ethnic cleavages. An important part in this is the work NGOs are doing in developing and fostering alternative migration narratives as well as actively countering xenophobic narratives.

Our research into alternative narratives around 2015 highlighted key narratives as well as those who develop and foster them: civil society organisations, NGOs, ethnic immigrant minorities, etc. Our work shows that (1) such narratives, even when they arise from marginalized positions, have a chance of succeeding, (2) that there is more than one way for narratives to achieve success, and (3) that there are factors that make such success more likely.

This particular part of BRIDGES studied alternative narratives about migration developed by civil society organisations in Germany, Italy and Spain. Our work began by mapping/finding organisations/voices that were active around/during and after the so-called crisis of 2015 and understanding their aims/motives, organisational structure, communicative strategies and alliances.

Mobilising, combining or bundling forces – as in the prominent cases of Seebrücke, Stop Mare Mortum or RegularizaciónYa – is a decisive factor for their success. Larger and highly diverse platforms are often sluggish, prone to dissolve or become unmanageable due to internal conflict, lengthy deliberation or other features of their structures. Strategies for mitigating these risks are crucial to the resilience of such organisations and the narratives they produce. In their own ways, all initiatives studied have struggled with these obstacles, either because they forged tenuous alliances between pre-existing organisations that eventually faltered (e.g., the platform Io Accolgo) or because they bypassed pre-existing organisations to tap into local potentials of activism (Seebrücke). Either strategy represents a challenge and requires familiarity with the local political and societal structures as well as communication skills. However, it can work extremely well in situations that seem like a dead-end, political stalemates that have not moved in years, or highly polarised debates.

Bottom-up organising and mobilising – i.e., from local to regional to national levels – can be an effective way to communicate more directly and successfully in local contexts than a fixed national campaign. This does not require the complete absence of centralised structures in the NGOs; working groups or committees may coordinate local chapters, provide cohesion at the national level, and facilitate exchanging experience. Ultimately, the combination of bottom-up and top-down forms of organising is exemplified by Seebrücke’s agile management and communication strategies as well as by its flexible approach to migration narratives, combined with key centralised elements and steering practices.

A third important finding indicates that windows of opportunity are critical success factors regarding the timing of narrative production. When windows of opportunity present themselves, being able to seize them quickly and effectively may depend on having at one’s disposal the necessary resources. Keeping the momentum of success seems equally related to capacities and funding; many initiatives face the threat of ‘fizzling out’ after initial successes or once their initial window of opportunity closes. Thus, it is important to distinguish time-sensitive opportunities from structural ones, and to strategise accordingly.

Regarding the content of migration narratives, initiatives need to carefully select and combine alternative narratives and counter-narratives to work within a specific national context and political moment. This may involve strategically foregrounding one type of narrative for a period of time, while background more the other type; for example, a visionary counter-narrative about achieving long-term change globally may need to be backgrounded – but still retained – in order to achieve immediate narrative success with a short-term-oriented alternative narrative, or vice versa.

In conclusion, we note that alternative, more inclusive narratives as well as more inclusive discursive practices, launched and propagated from non-hegemonic positions, can be successful under specific conditions and using context-aware strategies in windows of opportunity as they arise. This is precisely why there is no one-size-fits-all approach to successful campaigns, making it difficult to discern such patterns. As we hope to demonstrate, a case study-based European perspective sharpens our analytical gaze.